What is design thinking

1. What is Design Thinking?

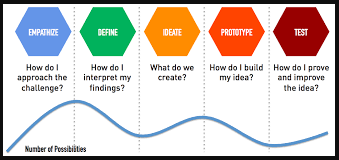

In employing design thinking, you’re pulling together what’s desirable from a human point of view with what is technologically feasible and economically viable. It also allows those who aren't trained as designers to use creative tools to address a vast range of challenges. The process starts with taking action and understanding the right questions. It’s about embracing simple mindset shifts and tackling problems from a new direction.

- Value-Centered Design

The Value-Centered Design focuses on attainable goals that add business value while improving user experience. It is rooted in the core values and offering of the business.

A Value-Centered Design approach can help identify and prioritize (feasibility) some of the users’ needs (desirability) when matched against the company’s goals (viability). As such, making it easier for merchants to set up and manage shops, and optimizing the customers’ checkout process would make excellent value-centered focus items. In addition to being balanced, this approach is powerful because it’s about designing with intention.

Let’s take Company A as an example, an e- commerce platform aiming at democratizing the eCommerce space by enabling merchants to sell their products through its system while exposing their wares to a wider audience.

From a Business-Driven Perspective, Company A’s main goal would be to increase the number of sales completed through their system, in order to increase its commission-based profit.

From a User-Centered Perspective, merchants desire easier access to the platform, easier inventory management, smaller fees, while customers desire easier access to relevant products, faster purchasing process, faster and cheaper deliveries. A value-centered approach would take into consideration the objectives of both the business goals while producing end results that meet the user’s needs as well.

As one iterates towards a final solution, the value-centered design framework which is based on the Design Thinking principle requires us to reassess with the goal of delivering appropriate, actionable, and Tangible strategies. The result is new innovative avenues for growth grounded in business viability and market desirability.

History of Design Thinking

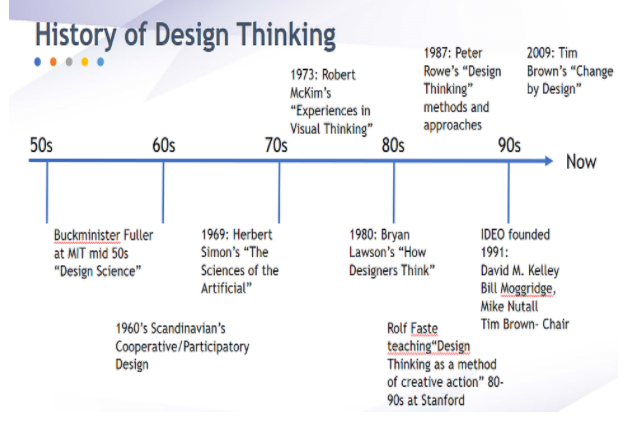

Listing all of the influential factors that have led to the contemporary understanding of Design Theory, Process, and Practice is almost impossible. Business analysts, engineers, scientists, and creative individuals have been focused on the methods and processes of innovation for decades.

Although more within the context of the architecture and engineering fields, early glimpses and references to Design Thinking date back to the '50s and '60s, and struggled to grapple with the rapidly changing environment in those times. New approaches to solving complex problems had their roots in the thinking applied to World War II, an event that had a profound effect on strategic thinking in the modern world and fundamentally changed the way we apply ourselves to management, production, and industrial design

In the struggle to fully understand every aspect of design, its influences, processes, and methodology, in the ’60s, efforts were made to develop a science out of the field of design, by applying scientific methodology and processes to understanding how design functions.

Nigel Cross, Emeritus Professor of Design Studies at The Open University, UK, in the paper Designerly ways of knowing: design discipline versus design science (2001), unpacks the struggle that began to unfold in the early 1960s when attempts were made to “scientist” design, and bring the field within the objective of rational sciences.

Cognitive scientist and Nobel Prize laureate for economics, Herbert Simon, have contributed many ideas that are now regarded as tenets of Design Thinking in the 1970s. He is noted to have spoken of rapid prototyping and testing through observation, concepts that form the core of many design and entrepreneurial processes right now. This also forms one of the major phases of the typical Design Thinking process.

Human-Centered Design

Since the early 1990s, Human-Centered Design and User-Centered Design were often interchangeable terms regarding the integration of end-users within a design process. Human-centered design only started to revolve around the late 1990s, when the development of methods described above shifted from a techno-driven focus to a humanized one. It was also at this point that we found ourselves with a design methodology that was manifested as more of a mindset than a physical set of tools.

A broader perspective of the ‘User ‘ was introduced in this context - One that is closely related to service design but situated in a broader, more socially conscious arena. In its final (and current) phase of evolution, HCD is seen to hold potential for resolving wider societal issues.

The broad holistic perspective introduced in service design allowed for human-centered design to redefine its meaning. Coupled with significant social and environmental disasters, it was appropriate after the turn of the millennium that HCD transformed from a method to a mindset, aiming to humanize the design process and empathize with stakeholders. The mindset approach of human-centered design re-introduced design thinking, but this time as a mindset used as a method for interpreting wicked problems.

2. Importance of Design Thinking

Successful businesses are making billions by recognizing the value of integrating design thinking into their process. The proof is in the numbers. Businesses have slowly come around to recognize that design can be used as a differentiator to respond to changing trends and consumer behaviors. Time and time again, Fortune 500 names such as Apple, Microsoft, Disney, and IBM have demonstrated the intrinsic value of design thinking as a competitive advantage that impacts the bottom line and drives business growth.

They’ve come to recognize that design innovation happens at the intersection of desirability for customers, viability at the business level, and feasibility for technology. Design thinking, a product design approach that has been slowly evolving since the 1950s integrates all three.

Business Value of Design Thinking

All businesses have a never-ending list of goals, from constantly releasing new products that increase sales by resonating with customers to providing better customer support.

When a business decides on a new product, a massive, expensive machine shifts into high gear, especially at large corporations. The costs are enormous. Applying design thinking can help save vast amounts of money right away because it directs attention to the specific solutions people need—immediate cost savings are realized as part of the ROI of design thinking.

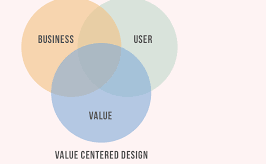

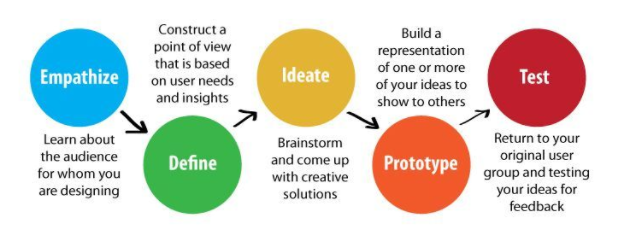

The Five Primary Steps that Promote Design Thinking in Business is:

- Empathizing : With the customers

- Defining : The challenges, needs, and wants

- Forming Ideas : Different approaches are taken to come up with solutions for the problem

- Prototyping : Products are made based on the different approaches

- Testing : Here the prototypes are tested and the faults plus benefits of the products are carefully studied

Design thinking provides a simple way to hone in on exactly what the problems are, often discovering a different way of thinking about them while also providing insights and data that are critical to building appropriate solutions that make the business money.

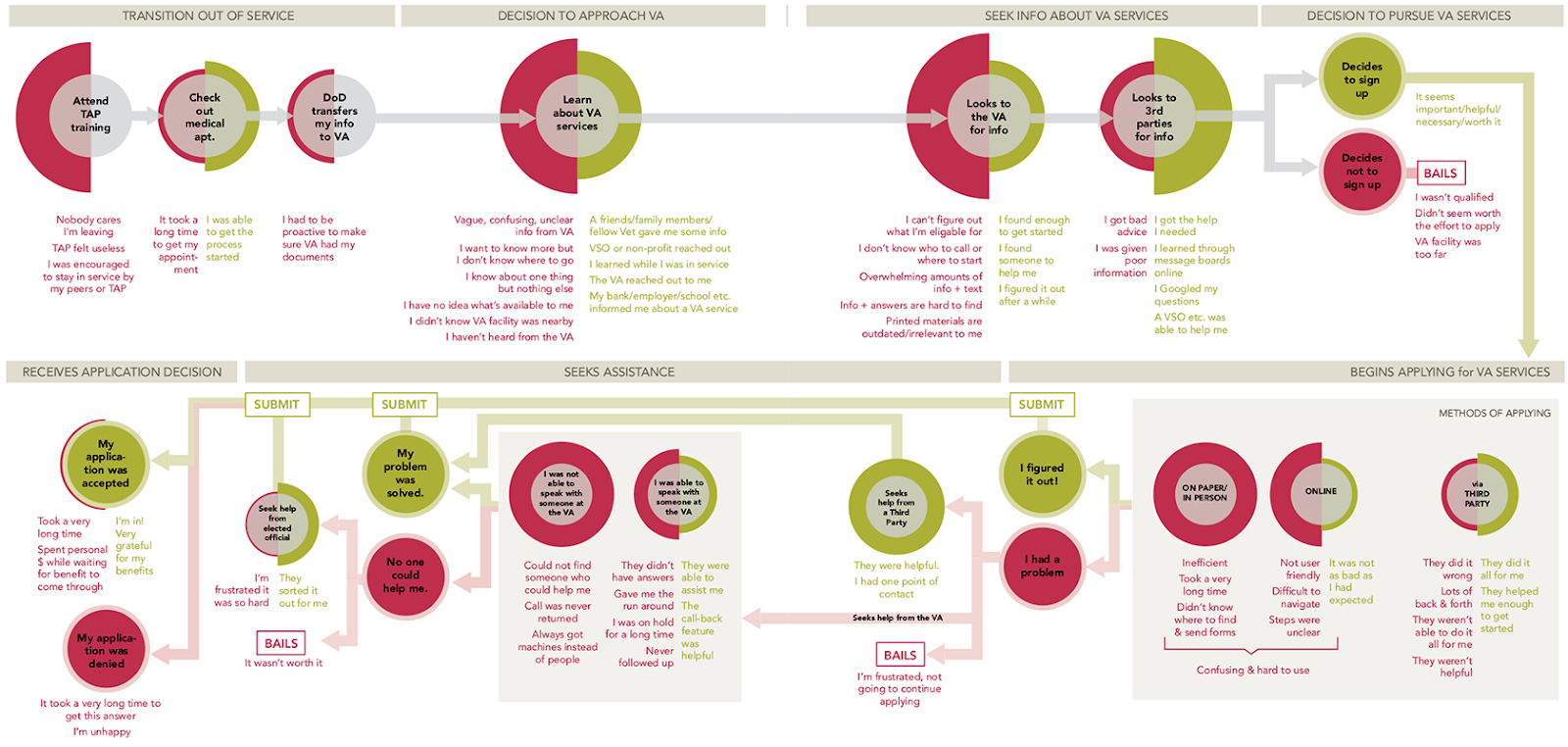

Government agencies also realize huge cost savings as a result of design thinking. The US Department of Veterans Affairs Center for Innovation began using customer journey maps to better understand how veterans were interacting with the VA. This simple exercise led to a better understanding of the difficulty veterans experienced when working with the VA and provided insight into how VA employees could better empathize, connect with veterans, and work more efficiently.

Substantial cost savings were realized by this new, streamlined, more efficient system, by improving the VA’s user experience as an outgrowth of design thinking. Waste was reduced because fewer interactions were needed by VA employees in order to efficiently serve veterans.

Customer Journey Map to VA Services by the US Department of Veterans Affairs

While every business is different, the first step to understanding how design thinking can help a business is to consider the challenges it’s currently facing.

What are they, and are there solutions already available that match a business’s needs and budget? If not, why? What are the things prohibiting those solutions, and where do those blockers stem from? Design thinking breaks down complex issues into tangible ones that can be analyzed and solved.

Reasons to Invest in Design Thinking & ROI

- Improving your UX saves you money

- A little up-front UX research can save you hundreds of engineering hours and thousands of dollars

- Decreases the cost of customer support

- Focusing on UX increases your revenue

- Increases conversion rates

- Improves customer retention and loyalty

Insisting on great UX drives competitive advantage and affects the bottom line. Just look at Dyson, Uber, Mint, Apple, IBM, and Intuit.

Measuring the Return On Investment (ROI) of design thinking can be a challenge in any organization. More challenging still, the changes to your business’s operations may not directly reflect the product’s overall change in performance compared to the previous workflow.

However, many cases show very clear signs that a design thinking methodology provides significant, positive change throughout the organization.

When Intuit established a new policy where employees could spend 10% of their time working on side projects, some of these employees questioned the purchasing policy for TurboTax back in 2007. They found that the company focused on selling five seats for the software, but most users only ever purchased one. Changing that focus resulted in a $10 million boost in sales of TurboTax in the first year.

Design Thinking doesn’t guarantee better products or solutions. Instead, it drives experimentation, data gathering, and analysis, and empowers designers to view their daily challenges in new ways. The results are promising. Moving from the “standard” model to one following user-centered design processes is a smart way to invigorate any organization to be faster, more organized, and more creative—all of which in turn drives a greater return on investment.

Startup companies that adopt the design thinking methodology tend to do better than their peers when it comes to fundraising and profits. Uber, Airbnb, War by Parker, and Etsy have achieved great success and have a history of design thinking in their methodologies. Over time, these brands outperformed their peers and their investors realized a greater return on their investment.

3. Why Design Thinking Works?

Occasionally, a new way of organizing work leads to extraordinary improvements. Total Quality Management did that in manufacturing in the 1980s by combining a set of tools—Kanban cards, Quality Circles, and so on—with the insight that people on the shop floor could do much higher level work than they usually were asked to. That blend of tools and insight, applied to a work process, can be thought of as a social technology.

In a recent seven-year study in which we have looked in-depth at 50 projects from a range of sectors, including business, health care, and social services, it has been identified that another social technology, design thinking, has the potential to do for innovation exactly what TQM did for manufacturing: unleash people’s full creative energies, win their commitment, and radically improve processes.

By now most executives have at least heard about design thinking tools—ethnographic research, an emphasis on reframing problems and experimentation, the use of diverse teams, and so on—if not tried them. But what people may not understand is the subtler way that design thinking gets around the human biases (for example, rootedness in the status quo) or attachments to specific behavioral norms (“That’s how we do things here”) that time and again block the exercise of the imagination.

Challenges of Innovation

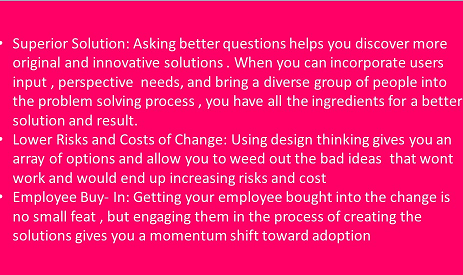

To be successful, an innovation process must deliver three things: Superior Solutions, Lower Risks and Costs of Change, and Employee Buy-In. Over the years business, people have developed useful tactics for achieving those outcomes. But when trying to apply those, organizations frequently encounter new obstacles and trade-offs.

Superior Solutions

Defining problems is obvious, conventional ways, not surprisingly, often lead to obvious, conventional solutions. Asking a more interesting question can help teams discover more original ideas. The risk is that some teams may get indefinitely hung up exploring a problem, while action-oriented managers may be too impatient to take the time to figure out what question they should be asking.

It’s also widely accepted that solutions are much better when they incorporate user-driven criteria. Market research can help companies understand those criteria, but the hurdle here is that it’s hard for customers to know they want something that doesn’t yet exist.

Finally, bringing diverse voices into the process is also known to improve solutions. This can be difficult to manage, however, if conversations among people with opposing views deteriorate into divisive debates.

Lower Risks and Costs

Uncertainty is unavoidable in innovation. That’s why innovators often build a portfolio of options. The trade-off is that too many ideas dilute focus and resources. To manage this tension, innovators must be willing to let go of bad ideas—to “call the baby ugly,” as a manager in one of my studies described it. Unfortunately, people often find it easier to kill the creative (and arguably riskier) ideas than to kill the incremental ones.

Employee Buy-in

Innovation won’t succeed unless a company’s employees get behind it. The surest route to winning their support is to involve them in the process of generating ideas. The danger is that the involvement of many people with different perspectives will create chaos and incoherence.

Underlying the trade-offs associated with achieving these outcomes is a more fundamental tension. In a stable environment, efficiency is achieved by driving variation out of the organization. But in an unstable world, variation becomes the organization’s friend, because it opens new paths to success.

The Beauty of Structure

Experienced designers often complain that design thinking is too structured and linear. And for them, that’s certainly true. But managers on innovation teams generally are not designers and also aren’t used to doing face-to-face research with customers, getting deeply immersed in their perspectives, co-creating with stakeholders, and designing and executing experiments. Structure and linearity help managers try and adjust to these new behaviors.

Organized processes keep people on track and curb the tendency to spend too long exploring a problem or to impatiently skip ahead. They also instill confidence. Most humans are driven by a fear of mistakes, so they focus more on preventing errors than on seizing opportunities. They opt for inaction rather than action when a choice risks failure. But there is no innovation without action—so psychological safety is essential. The physical props and highly formatted tools of design thinking deliver that sense of security, helping would-be innovators move more assuredly through the discovery of customer needs, idea generation, and idea testing.

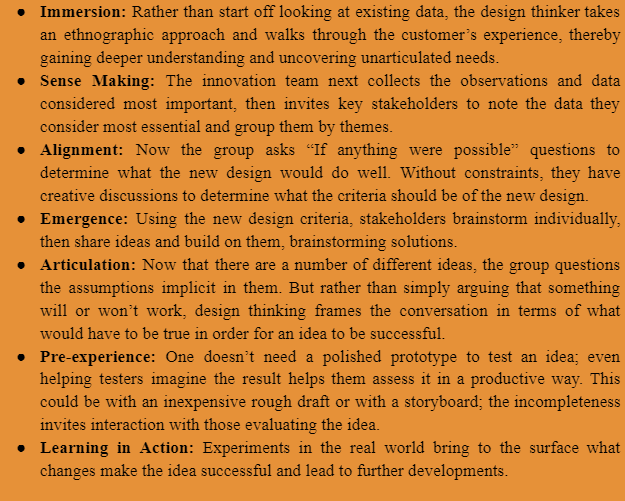

In most organizations, the application of design thinking involves seven activities. Each generates a clear output that the next activity converts to another output until the organization arrives at an implementable innovation. But at a deeper level, something else is happening—something that executives generally are not aware of. Though ostensibly geared to understanding and molding the experiences of customers, each design-thinking activity also reshapes the experiences of the innovators themselves in profound ways.

Customer Discovery

Many of the best-known methods of the design-thinking discovery process relate to identifying the “job to be done.” Adapted from the fields of ethnography and sociology, these methods concentrate on examining what makes for a meaningful customer journey rather than on the collection and analysis of data. This exploration entails three sets of activities:

Immersion

Traditionally, customer research has been an impersonal exercise. An expert, who may well have pre existing theories about customer preferences, reviews feedback from focus groups, surveys, and, if available, data on current behavior, and draws inferences about needs. The data through the lens of their own biases. And they don’t recognize needs people have not expressed. Design thinking takes a different approach: Identify hidden needs by having the innovator live the customer’s experience. Consider what happened at the Kingwood Trust, a UK charity helping adults with autism and Asperger's syndrome. One design team member, Katie Gaudion, got to know Pete, a nonverbal adult with autism. The first time she observed him at his home, she saw him engaged in seemingly damaging acts—like picking at a leather sofa and rubbing indents in a wall. She started by documenting Pete’s behavior and defined the problem as to how to prevent such destructiveness.

But on her second visit to Pete’s home, she asked herself: What if Pete’s actions were motivated by something other than a destructive impulse? Putting her personal perspective aside, she mirrored his behavior and discovered how satisfying his activities actually felt. “Instead of a ruined sofa, I now perceive Pete’s sofa as an object wrapped in fabric that is fun to pick,” she explained. “Pressing my ear against the wall and feeling the vibrations of the music above, I felt a slight tickle in my ear whilst rubbing the smooth and beautiful indentation…So instead of a damaged wall, I perceived it as a pleasant and relaxing audio-tactile experience.”

Sense-Making

Immersion in user experiences provides the raw material for deeper insights. But finding patterns and making sense of the mass of qualitative data collected is a daunting challenge. Time and again, I have seen initial enthusiasm about the results of ethnographic tools fade as non-designers become overwhelmed by the volume of information and the messiness of searching for deeper insights. It is here that the structure of design thinking really comes into its own.

One of the most effective ways to make sense of the knowledge generated by immersion is a design-thinking exercise called the Gallery Walk. In it, the core innovation team selects the most important data gathered during the discovery process and writes it down on large posters. Often these posters showcase individuals who have been interviewed, complete with their photos and quotations capturing their perspectives. The posters are hung around a room, and key stakeholders are invited to tour this gallery and write down on Post-it notes the bits of data they consider essential to new designs. The stakeholders then form small teams, and in a carefully orchestrated process, their Post-it observations are shared, combined, and sorted by theme into clusters that the group mines for insights. This process overcomes the danger that innovators will be unduly influenced by their own biases and sees only what they want to see because it makes the people who were interviewed feel vivid and real to those browsing the gallery. It creates a common database and facilitates collaborators’ ability to interact, reach shared insights together, and challenge one another’s individual takeaways—another critical guard against biased interpretations.

Alignment

The final stage in the discovery process is a series of workshops and seminar discussions that ask in some form the question If anything were possible, what job would the design do well? The focus on possibilities, rather than on the constraints imposed by the status quo, helps diverse teams have more collaborative and creative discussions about the design criteria or the set of key features that an ideal innovation should have. Establishing a spirit of inquiry deepens dissatisfaction with the status quo and makes it easier for teams to reach consensus throughout the innovation process. And down the road, when the portfolio of ideas is winnowed, agreement on the design criteria will give novel ideas a fighting chance against safer incremental ones.

Consider what happened at Monash Health, an integrated hospital and health care system in Melbourne, Australia. Mental health clinicians there had long been concerned about the frequency of patient relapses—usually in the form of drug overdoses and suicide attempts—but consensus on how to address this problem eluded them. In an effort to get to the bottom of it, clinicians traced the experiences of specific patients through the treatment process. One patient, Tom, emerged as emblematic in their study. His experience included three face-to-face visits with different clinicians, 70 touchpoints, 13 different case managers, and 18 handoffs during the interval between his initial visit and his relapse.

The team members held a series of workshops in which they asked clinicians this question: Did Tom’s current care exemplify why they had entered health care? As people discussed their motivations for becoming doctors and nurses, they came to realize that improving Tom’s outcome might depend as much on their sense of duty to Tom himself as it did on their clinical activity. Everyone bought into this conclusion, which made designing a new treatment process—centered on the patient’s needs rather than perceived best practices—proceed smoothly and successfully. After its implementation, patient-relapse rates fell by 60%.

Design Thinking typically involves seven steps along the path from customer discovery to idea generation to the innovative result itself.

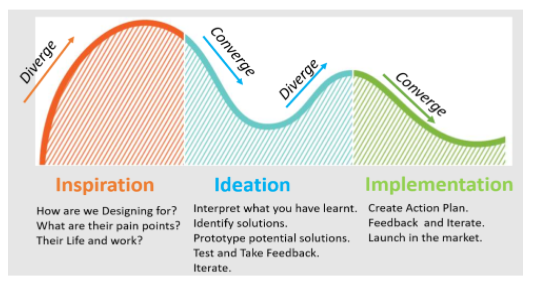

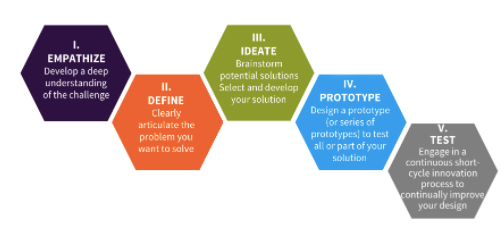

4. Stages of Design Thinking

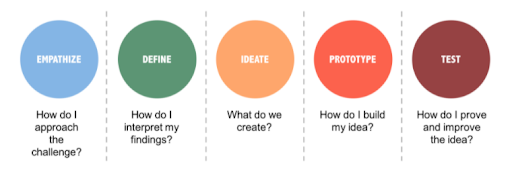

Empathize

The first stage of the Design Thinking process is to gain an empathic understanding of the problem you are trying to solve. Empathy is crucial to a human-centered design process such as Design Thinking, and empathy allows design thinkers to set aside their own assumptions about the world in order to gain insight into users and their needs.

Depending on time constraints, a substantial amount of information is gathered at this stage to use during the next stage and to develop the best possible understanding of the users, their needs, and the problems that underlie the development of that particular product.

Define

During the Define stage, you put together the information you have created and gathered during the Empathize stage. This user research should seek to identify the wants and needs of the end user in relation to a particular problem. The goal of this stage is for the team behind the improvement project to ‘become the user’, setting aside their own pre-existing assumptions about the problem in order to outline the unmet or unarticulated needs of those actually experiencing it.

Ideate

This stage of the Design Thinking process is all about idea generation. Here, teams use the information gained during the previous stages to form logical ideas. The intention is to brainstorm as many ideas as possible, thinking “outside of the box” to identify possible solutions to the problem-statement that was defined in the previous stage. Adopting the mentality that ’there are no bad ideas’ from the outset of this stage enables teams to engage in free-thinking and expand the problem space. During the end of the ideation process, teams shortlist the best ideas for solving the problem.

Prototypes

This stage is focused on experimentation and is an opportunity to learn by doing. Here, the team will produce numerous scaled-down versions of the subject of the improvement project or features found within it based on the shortlist defined during ideation. It is important to note that this stage is not about validating finished ideas, but about improving, re-examining or rejecting the ideas created in the previous stages on the basis of the users’ experiences.

Test

The fifth and final stage is an iterative process. Here, the team tests the prototypes created in the previous stage to see how well they address the problem identified during stages one and two. The results generated during this stage may be used to make alterations and refinements, and even redefine the problems or further inform the understanding of the users involved. The team may continue to work on this stage until they have the result they desire.